New social groups and the new paradigms they embody emerge first as a kind of new social mentality, which grows quietly within the silent changes of the mode of production, the social structure, and the political situation. At the outset, there is no name for what is developing, and things slowly become a trend, which is often understood in terms of deviance, because once people notice it, they often describe it in negative terms. This turn pushes the new social group toward self-awareness. The rise of the Little Pinks and the new patriotism went through just such a process.

A major phenomenon we observe in China’s public opinion today is a serious rupture between the emerging ideological trends in online youth behavior and the Chinese intellectual milieu. Traditional academic categories of analysis, such as debates between left and right, enlightenment and conservatism, elitism and populism, nationalism and universalism (liberalism), authoritarianism and liberal democracy, the market economy and the planned economy, are gradually losing their explanatory power. In the past, the opposing sides kept calling for an imaginary “common baseline” that would transcend left and right, but in reality the quarrels have continued. Transcendence was elusive within the old cognitive framework, but in recent years, a series social-ideological trends has emerged from within youth subculture, grounded in current tensions and seeking to transcend the left-right divide, among which the “technology party”[2] (or “industrial party” 工业党), the Little Pinks 小粉红, and the “barbarians at the gate 入关学” group are the chief representatives. Among these, the Little Pinks can be said to be the largest group.

“Little Pinks” broadly refers to the new generation of patriotic young people born after 1990 who have grown up deeply embedded in the modern market economy and urban life—but their name was chosen by their rivals. Following a series of major public events on the international scene in 2008, what had formerly been debates between the left and the right, chiefly carried out by intellectuals on China’s Internet, gradually gave way to debates between the patriotism of ordinary netizens and “universal values.” The main parties to the conflict are respectively the “America-supporting public intellectuals 公知美分” and the “Self-Financing Fifty-Cent Army 自干五.” The predecessors of the Little Pinks, the “Jinjiang young women’s Group for National Awareness 晋江忧国少女团” and the “Fengyi Sisters 凤仪妹子,” appeared as early as 2010, when Big V celebrity intellectuals still dominated China’s Internet.

Those connected with Jinjiang Girls and Fengyi Sisters were mainly female netizens who were active on literature and entertainment websites, were fashionable and patriotic, and opposed to public intellectual groups who blindly worshiped the West and belittled China. At the outset, the Little Pinks were a minor sub-branch of the “Self-Financing Fifty-Cent Army,” but some prominent public intellectuals, understanding that they were dealing with new opponents who were unlike traditional leftists, derisively branded them “Little Pinks.” The group grew quickly, the name “Little Pinks” having produced an explosion of self-consciousness. In 2013, the online celebrities and public intellectuals who talked about “universal values” on social media began to decline, while the fame of the “Little Pinks” continued to rise, gradually transforming the online public opinion environment formerly dominated by public intellectuals. In January 2016, the Little Pinks carried out a flood attack on Facebook, which shocked public opinion both at home and abroad.

The mainstream attitude of traditional intellectuals and media circles towards the Little Pinks is negative and suspicious, and a large number of liberal intellectuals criticize them for having merely a “high school educational level,” saying they exhibit “excess libido and a hyperactive spirit,” all coming from the “lowest rung” of society. They see the Little Pinks as the product of a mentality of “loyalty” and “hatred,” and sadly discuss the return of “ultra-left” and the “failure of thirty years of enlightenment.”

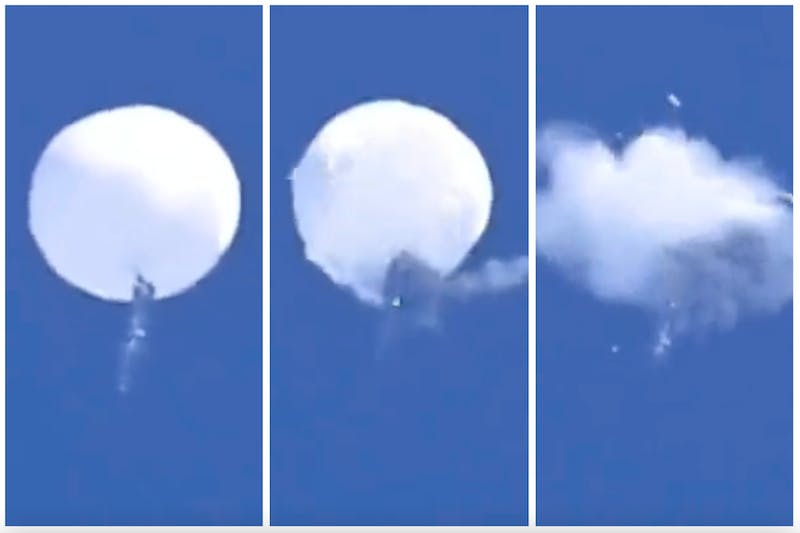

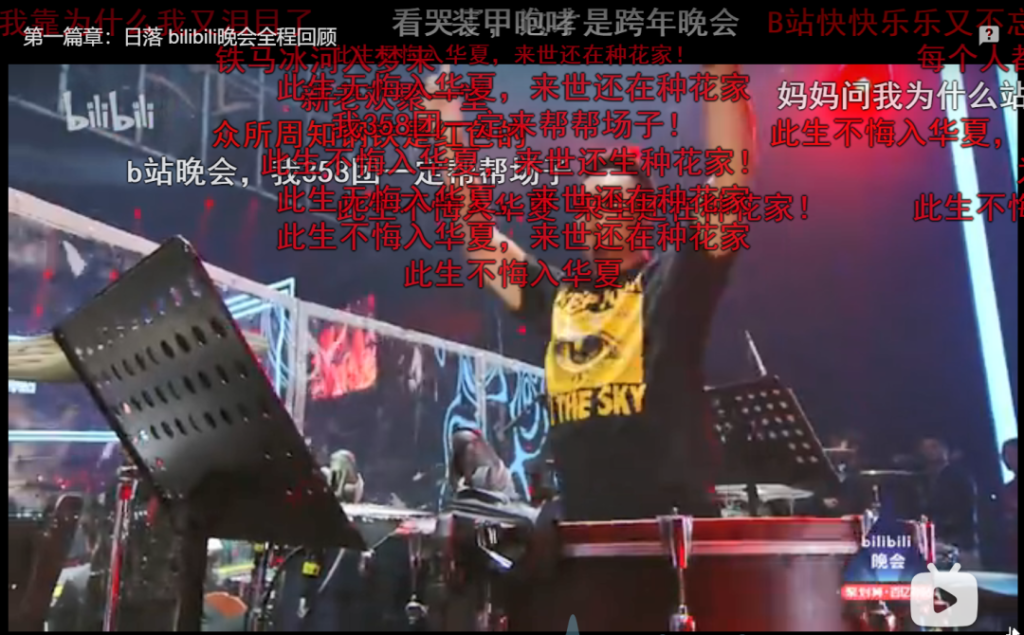

However, the Little Pinks quickly became mainstream in online public opinion. This mainstreaming was visible at the end of 2019, when the Bilibili website hosted its first New Year’s Eve party. Accompanying the song the “Flower Suite 种花组曲,” the screen filled with the words “I do not regret being born in China in this life, and I will choose to be born in China in my next life, too.”

The mainstream of youth politics on Bilibili is notably “pink.” For example, in 2019, Fang Kecheng 方可成, a well-known contributor (UP主) to the site, was identified by netizens as someone who was leaning toward Hong Kong independence. He left the website after receiving a barrage of criticism. In 2020, the well-known popular science contributor “Paperclip” posted a video that was found by netizens to be insulting to China, leading to repeated boycotts by netizens and the closure of the account.

The Little Pinks are China’s “revival generation,” rising out of difficult circumstances. Their ideas are a complex mixture that seems to include nationalism, conservatism, and certain left-wing themes, the common thread of which is to oppose American “universal values,” and thus they are often seen as the opposite of liberalism or 1980s’ style “enlightenment.” But liberalism and the Little Pinks are not really rivals, because the ideas expressed by the Little Pinks do not completely follow the trajectory of the traditional pendulum swings of left and right, but contain new elements.

Critics have argued that the Little Pinks are the product of a new globalized media business culture, and that in this sense they may be more universal than their ostensibly “universal” enemies. Their mode of action, style of discourse, and emotional reactions are all rooted in the globalized market economy, even if one of their characteristics is to exhibit a kind of “anti-globalization (i.e., nationalist) globalization.” We need to understand the Little Pinks in this broader context, which in turn will help us understand the ideological trends displayed by contemporary Chinese youth.

Three Waves of New Youth Patriotism

The “new patriotism” of the Little Pinks is starkly different from past displays of patriotism. In order to see the Little Pinks in a broader perspective, we will begin with a simple genealogy of three waves of youth patriotism that arose since 2008.

The first wave was spearheaded by patriotic groups of overseas students. These students had been living abroad for some time, meaning that their understanding of Western society had progressed from imagination to personal experience, leading them to grasp the huge gap between Western myth and Western reality. These groups originally came together on overseas student platforms like Xixihe 西西河, and came to the fore in the context of various international political disturbances involving China in 2008, such as efforts to protect the Chinese Olympic torch relay runners in Europe, or opposing the distorted coverage of China by Western media such as CNN. Participants were relatively elite, highly educated, and had sophisticated language skills, and expressed themselves on the anti-CNN website (later renamed the “April website”) and other sites exclusively devoted to these themes.

Following the rise of social media in 2010, the groups moved to Weibo, using identifiers beginning with AC (short for anti-CNN), thus becoming one of the seeds of new patriotic youth power in the social media era. This wave of patriotic youth no longer engaged in glamorized fantasies of the West, but sought to transmit real experiences to the Chinese people. A series of articles by “Little Water Bottle 小水瓶,” a Peking University student studying abroad, were typical. One article, “Is China’s Health Care Worse than America’s? Should We Swap?” not only compared healthcare in China and the United States, but also singled out Han Han 韩寒 (b. 1982), a liberal youth leader and popular blogger at the time, for his lack of genuine experience of life in the West. In general, at this stage, Little Pinks were seeking to define themselves through questioning and confrontation.

The second wave began in 2010. At that time, the “Arab Spring” and the “Twitter Revolution” were on the rise, sentiment on China’s social media was fluid, and the “stock” of Western universal values seemed to be at its peak. Some Chinese elites with experience in living, working, or media engagement outside of China, including experts, scholars, and social activists, joined together with the first wave of overseas students and patriotic youth in China to carry out organized resistance to the West through media and other means. In June 2011, the Shanghai Chunqiu Institute for Development and Strategic Studies 春秋战略发展研究院, a private think tank, in cooperation with Shanghai Wenhui Daily 文汇报, organized a “Debate of the Century” between Zhang Weiwei 张维为 (b. 1957) and American political scientist Francis Fukuyama (b. 1952), declaring the end of the “end of history.”

Subsequently, the Guancha Syndicate, an outgrowth of the Chunqiu Institute, began to take the lead in online public opinion. In a series of initiatives, such as their defense of China’s development of high-speed rail, their opposition to the “Washington Consensus,” their debunking of certain Western myths, their affirmation of China’s development advantages, and their advocacy for the “China Model, Guancha continuously expanded its influence and attracted a large number of elite writers to join in, and in the process replaced the April website and became the banner of new patriotic media.

At this stage, the discursive tone of the new patriotism became more positive, emphasizing the successful nature of China’s development experience, and displaying a clear self-consciousness that China’s path was distinct from that of the West. Another important phenomenon emerged at this stage: a group of young opinion-makers working in science and engineering, who used to belong to the “silent majority,” but who now entered mainstream public opinion with the help of new media such as Guancha, seeking to update the obsolete model of political discourse based on left and right antagonisms with a new developmental discourse grounded in the actual workings of science and technology. This group was called the “technology party.” As a “self-made” group within China’s new middle class, they expanded both the social basis and the theoretical strength of the new patriotism.

At this stage, the discursive tone of the new patriotism became more positive, emphasizing the successful nature of China’s development experience, and displaying a clear self-consciousness that China’s path was distinct from that of the West. Another important phenomenon emerged at this stage: a group of young opinion-makers working in science and engineering, who used to belong to the “silent majority,” but who now entered mainstream public opinion with the help of new media such as Guancha, seeking to update the obsolete model of political discourse based on left and right antagonisms with a new developmental discourse grounded in the actual workings of science and technology. This group was called the “technology party.” As a “self-made” group within China’s new middle class, they expanded both the social basis and the theoretical strength of the new patriotism.

The third wave was the emergence of the Little Pinks. The Little Pinks are no longer part of the intellectual elite, but were instead the youth reserve army of the new urban middle class, which further expanded the base of the new patriotism. Compared with the earlier two waves of patriotic groups, the Little Pinks were younger, the proportion of women was greater, links to daily life were clearer, and they appealed to many fan groups, for example, female fashion groups like Jinjiang and the Fengyi forum. There were male Little Pinks as well, many coming from sports and gaming fan groups by way sites like of Diba, Hupu, and Bilibili.

In terms of ideas, the Little Pinks’ are less theoretical and political in comparison with the two previous waves, when people were more self-conscious about their “keyboard politics.” The Little Pinks drew intuitively on their life experience. They have less historical baggage and do not share the previous generations’ memories of the twin shocks of the Cultural Revolution, and then the transformation brought on by China’s reform and opening. The miracle of China’s rise since 2008 leads them to feel that China is developing faster than the West, and that life in China is more convenient, public security is better, industry is stronger, and management of the pandemic better, all of which has generated a pure sense of national pride.

In terms of their modus operandi, their engagement in commercial fan culture has allowed them to develop organizing skills, such as “supporting idols” and attacking enemies – skills that the first two waves of patriotic youth groups did not possess. Its decentralized online style of mobilization is different from the elite-driven action styles of international students or the intellectual community, but it is linked to and interacts with the first two waves as well.

It is worth noting that the development of the mobile Internet allowed more and more young people from third- and fourth-tier cities to join the ranks of the Little Pinks. These new members bring with them many economic and cultural differences, so today’s Little Pinks are quite a heterogeneous group.

The Little Pinks as Cultural Contradiction

Socialist practice in contemporary China is a messy contradiction of individualism, consumerism, socialism, conservatism, and even internationalism. The phenomenon of the Little Pinks embodies a similar mixture, but its external appearance, made up of nationalist identity and patriotism, can easily camouflage its intriguing internal contradictions.

National Identity Politics and the Cultural Self-Esteem of the New Middle Class

The Little Pinks patriotic movement, which spread widely on the Internet, embodies the consciousness of the new middle class of a consumerist society. It mobilizes the middle class, including students and white-collar workers, and its reserve army of young people. By way of contrast, previous patriotic movements tended to reach a broader base, as in anti-Japanese demonstrations, which until 2012 included grassroots people such as migrant workers, and displayed the characteristics of traditional anti-imperialist mass street politics and masculinity.

The Little Pinks patriotic movement grew out of events such as: a 2018 incident in which the Swedish police rough handled Chinese tourists; an advertisement by the Italian fashion brand Dolce & Gabbana that insulted China and spurred patriotic youth protests; web attacks on the Chinese-American director Chloe Zhao for allegedly publishing anti-Chinese comments in 2021; and attacks certain South Korean stars who allegedly insulted China, sparking the “no fan idols before the nation” movement in which fans declared their allegiance to China, and not to their idol. It is obvious that these events are concentrated in the fields of fashion, consumption, and culture. The emotional issue is that these incidents hurt the self-esteem of China’s young middle-class reserve army and its global fashion consumption power.

As a result, while the combined force of the Little Pinks’ actions points in the direction of the traditional grand narrative of nationalism, its widespread mobilizing power stems from a demand for middle-class national identity in the era of globalization (rather being a nationalist consciousness in a strict sense), and the point of this identity politics is to demand that the other side recognize that “I too am a civilized person, just like Westerners.” This passion for recognition has given birth to a form of identity politics that is nationalist in nature, but is not a characteristic of identity politics in Western societies.

Affective and Cognitive Modes in the Online Fictional World

Common emotions and shared interests are the ideological components of the lowest level of society, and the kinetic energy they generate is far larger than rational ideas. When we dive below the surface of the Little Pinks’ strong patriotic emotions, we find that the Little Pinks share some important contemporary ideological and emotional components with their rivals, the “universalists.” Among these are: “avoiding the sublime 躲避崇高,” life politics, postmodern playfulness, political correctness, and a broad sense of fragility, etc. At the same time, we also find heterogeneous elements, culminating in a unique “emotional identification and authentication mechanism.”

The generation that bade farewell to revolution rejected the Little Pinks, having failed to see that the younger generation had to a certain extent achieved their dreams without realizing it. The idea that “patriotism can be cute too,” and a politics based on shared interests makes the country and its history more interesting, producing new idols for fan clubs. For example, the webcomic Year Hare Affair 那年那兔那些事 presents various countries as cartoon images of animals, which actually accords with the 1990s proposition of “avoiding the sublime.” The difference is that the Little Pinks avoid the form of the sublime, while providing new forms and new outlets for it. The market economy will “remove the sublime” from daily life but as long as the struggle in contemporary world history is not over, “the sublime” will continue to reside in everyday culture.

The culture of online fiction itself contains a kind of structure guiding emotional practice. In particular, fan-fiction recreates idol stories out of the authors’ own narratives, helping the fans to establish a flexible and interactive emotional imagination space around an idol, which builds a highly immersive “imagined community.” “Year Hare Affair ” and “Azhong Gege 阿中哥哥” have both absorbed the modes and emotional practice methods of fan-fiction, taking “country” as the object of fan creation and projecting emotion onto it, so that patriotism and great struggle can also participate in the competition of the emotional space of online fiction.

It has been widely noted that the Little Pinks’ patriotic feelings have developed into a form of political correctness that has the characteristic of being decidedly non-negotiable. “Grave digging” behavior is prominent: the use of social media to dig up people’s past inappropriate remarks about the country, and then to report the findings and accuse the person in question. People like the film director Chloe Zhao and the late pianist Fou Ts’ong 傅聪 (1934-2020) have been widely lambasted on social media for their pro-Western proclivities. Such criticisms often refuse to consider the context of the remarks, or that times and people change, and draw lines based on the current confrontation between the United States and China. How should we understand such behavior?

On the one hand, this kind of stereotyped and absolutist way of thinking is grounded in the fact that while adolescents may be quite experienced in daily consumption and entertainment activities, they lack experience in terms of the harsh struggle for survival and work in society. As a result, they have difficulty thinking about things in a complex and realistic manner, and are accustomed to identifying friends and enemies through speech and symbols, which leads to feelings and views that are little more than labels.

This is not nationalistic narrow-mindedness, but a modern disease affecting the whole world. A recently published book, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, explains in detail how American youth, damaged by political correctness and a culture of over-protection, have become increasingly sensitive and vulnerable to emotional harm, making them eager to “expose” and “report” evil-doings. They have been indoctrinated about “microaggressions” and are keen to censor the politically incorrect and intrusive behavior of those around them in their daily lives. The Little Pinks share this form of political correctness, but the content is different. In this sense, the Little Pinks and their “universal values” rivals are “discourse” people, identifying friends and enemies on the basis of ideas embodied in discourse, rather than empirical considerations. This should also make us wonder if the Little Pinks share the fragile psyche of American youth.

At the same time, it is important to note that it is precisely in the political sphere that emotion always functions as the most direct recognition mechanism, able to identify friend and foe more quickly than reason. Identity politics was originally a kind of politics of emotion, which depends on emotional experience in a specific situation. When international conflict is beyond the control of human beings, and when the defenders of “universal values” use words like “rationality” and “Enlightenment” to criticize the Little Pinks, and are unable to hide their own pro-Western emotional stance, it will be impossible to gain the respect of the other party. It is like when the Hong Kong virologist Guan Yi 管轶 (b. 1962), at the beginning of the pandemic, admitted that “I am afraid this time,” and that “even veterans like me want to desert.” Even if he was right in terms of his medical judgment, compared to the medical team that decided to go against the current and help Wuhan, Guan was attacked by young Internet users for clearly revealing his emotional stance.

The Attack of the Retail Investors: The Organizational Patterns of Fan Clubs

The fan-girl online attack [or “expedition” 出征] on pro-Hong Kong independence celebrities in August 2019 dramatically illustrates the similarities between the Little Pinks movement and the regular fan club movement, and the differences between the Little Pinks and past patriotic movements. In 1999, 2004, 2005 and 2012, anti-American and anti-Japanese movements developed into street marches, whose themes expressed popular desires in the context of major political debates, while the Little Pinks’ attack was a purely online movement: they divided up the tasks, wrote up the posts they were going to send, organized the vote and sought to win people to their side, made positive comments on their favorites and reported negative comments coming from the other side, all of which is rooted in the daily organization activities of various network interest communities.

“Attacks” are a common form of community organization produced by the global Internet economy. Similar organizational methods can be seen in the populism of Trump-era Twitter politics in the U.S., and in January 2021, when retail investors used Reddit to attack Wall Street in the GameStop incident. Retail investors are in one sense separated from traditional social units and institutions, but they do not remain in an “atomized” situation, and instead use the Internet to organize themselves.

This kind of united movement of retail investors is increasingly escaping the Internet, and affecting the organization and operation of the real world. The Xiao Zhan incident 肖战事件, which lasted from 2020 to 2021 and whose influence is still felt today, is a typical example of the socialization of the fan economy. At the outset, the Xiao Zhan incident was just an internal conflict within Xiao’s considerable fan group, but it triggered a chain reaction, and fans’ reports led to the blockage of the Archive of Our Own fan-fiction website, which in turn affected the daily entertainment activities of other fan groups. The struggle expanded, and Xiao Zhan himself became a target, and those who were against him adopted a typical consumerist tactic: boycotting the brands for which Xiao is a spokesman, which drew the luxury outlets into the game. As a result, fan groups, money, and the government all came to be involved.

Similar things have happened again and again. For example, in February 2021, there was a controversy on Bilibili over a Japanese anime called “Jobless Reincarnation” because of accusations of pornography. Originally, it was an argument within the fan club, but because a streamer on a Bilibili site made inappropriate comments about Chinese history, the Little Pinks joined in and attacked, which then led a Douban group of women activists to pitch in as well, trying to influence Bilibili’s share price. This reflects the unbalanced and unstable state of the youth cultural ecology, in which minor incidents often result in multi-party conflicts.

In July of 2021, just because a certain Chinese shoe and clothing brand “announced” it was going to donate 50 million RMB of items to the flood-stricken areas of Henan, patriotic netizens rushed into the brand’s live broadcast room to frantically buy their good and express their gratitude, a typical example of how the emotional Little Pink movement spreads instability through the Chinese economy.

Ecological Niche Rivals of the Little Pinks

After understanding the Little Pinks as a particular Chinese expression of a global phenomenon, we need to introduce the analytical perspective of the “ecological niche” to investigate its real position in social contradictions.

Traditional intellectuals who appear to vehemently reject the Little Pinks are not in the same ecological niche and thus do not constitute direct competition. Behind their apparent opposition, there is a generational “species division,” and the two groups do not understand each other due to differences in historical experiences and discourse systems. For example, when the Little Pinks criticized Fang Fang’s Diary, they used weapons such as rap, memes, and digital drawings, which those on Fang Fang’s side could not understand, which led to funny outcomes. Intellectuals’ angry denunciations of the Little Pinks often missed their mark and did not constitute true criticism.

Youth groups connected to Hong Kong independence and Taiwan independence occupy the same ecological niche as the Little Pinks. In 2019, the formerly invincible Diba was attacked by youth groups connected to Hong Kong independence. These youths are, like the Little Pinks, indigenous people of cyberspace, and fight using the same online methods as other fan groups, such as joining together on Internet platforms, dividing up the work and cooperating to hack into the Diba site and reveal the private information of members of rival groups. Once attacked, Diba repeatedly called for a truce. This allows us to see that different camps are generating new online species, each developing the organizational capacity of the retail investor in the era of globalization. They have similar fashion interests, modes of action and discursive weapons, despite their conflicting positions and ideas. To use a biological metaphor, they are all in the same “ecological niche,” meaning that they are in competition.

Once we understand where the Little Pinks stand in terms of “identity politics + national consciousness,” we can then better understand their entanglement with other identity politics movements in the public opinion ecology, such as their conflicts with feminism. In February of 2020, the Weibo account of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Youth League launched two virtual patriotic idols, “Red Flag Manga 红旗漫” and “Jiangshan Jiao 江山娇,” who were to host an online cartoon celebration of Made in China Day, which ended in controversy.

Among other things, the female character “Jiangshan Jiao” attracted a wave of feminist ire, and when asked to participate in the “100 Questions for Jiangshan Jiao” activity, feminists sent in questions like: “Jiangshan Jiao, do you menstruate? “Jiangshan Jiao, did the leader ask you to shave your head?” “Jiangshan Jiao, do you have a little brother because your parents did not want a girl?” They even made up rap songs to ridicule Jiangshan Jiao, which had a considerable impact. Like the Little Pinks, young feminists are immersed in the discourse of the globalized, media-oriented market economy and identity politics. They know how to skillfully use new media channels and new discursive means to spread their message. When feminists attacked the Bilibili site in February 2021 and in the second-hand smoke incident in Chengdu in April 2021, we can see the feminists fighting against male Little Pinks and Self-Financing Fifty Cent Army. This shows that Little Pinks have become deeply involved in what British sociologist Anthony Giddens (b. 1938) calls “life politics” rather than “traditional politics,” and that future challenges will mainly come from groups that occupy similar ecological niches in social life.

They are Their Own Worst Enemy

In 2020, many people noted the existence of a curious social mentality: young people are generally confident about the future of the country at the macro level, but pessimistic about their personal life prospects at the micro level, anxious about employment, marriage, and childbearing issues. What gave rise to this schizophrenic mentality?

The new patriotic emotion which is represented by the Little Pinks took root in the era of globalization and the market economy with socialist characteristics, which is subtly different from “short twentieth century” patriotism. The latter is based on the experience of suffering and a sense of responsibility, in the sense that although modern China was poor and weak, and was repeatedly bullied, patriots nonetheless “explored this vast land with their damaged hands.” The former is based more on the experience of national strength and personal happiness. This raises the question of whether feelings can be influenced by changes in living standards and experiences.

The greatest pandemic in a century has stunted economic development and reduced employment opportunities for young people. At the same time, as people who grew up on the Internet, the 1990s generation greatly relies on Internet platforms for work and life. Their personal life is becoming more “indoorsy 宅化,” and their ability to understand offline real life and pressures has decreased. They were born on the Internet and will die on the Internet. They are increasingly in the grip of a combination of consumerism, overtime culture, and debt culture. Now that the platform capital giants are trapped in their own involutional competition, further infiltrating all aspects of the people’s social lives, and turning from exploring new value space to harvesting users in all possible ways, young people’s impression of capital, especially platform capital, has deteriorated markedly. Jack Ma’s 马云(b. 1964) image has plummeted. Online youth cheered the premature death of Zuo Hui 左晖 (1971-2021), the founder of a well-known online brokerage platform.

At the same time, young people’s expectations of state-owned enterprises and state employment have increased, and they have begun to imagine good things about the planned economy. In this context, since 2020, we might note that young people’s interest in Marxism has increased exponentially. The site Bilibili has tons of short videos produced by tens of thousands of netizens on their own initiative, introducing Marxism and criticizing capitalists. The numbers of such videos have increased seven times since 2019. CCTV’s 2019 documentary “The Power of Capital” was originally intended to celebrate the glories of reform and opening, providing a positive overview of the construction of capitalism and markets. However, after being reposted to Bilibili, it was met with a barrage of critical comments. At the same time, sales of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong also surged in 2020.

Thus we should note that the Little Pink generation, while steeped in the market economy, still displays symptoms of late capitalism in its aversion to capital and its devotion to “video-clip Marxism.” Given their diminished life experience, their declining life expectations, their tendency to spend time online with likeminded people, their political correctness, their emotional manipulativeness, to which we might add the popularity of a morose depression culture and the usefulness of anxiety as a tool to drive media traffic…these factors together with the involution of global capital, have produced an emotional state in today’s youth that might be called a “patriotic, anti-imperialist, and anti capitalist + online grievance” culture. This may be one of the sources of the Little Pinks’ “schizophrenic mindset.” This is not so much a return of the left, but what Fukuyama calls the current “politics of resentment” among Western youth, the product of the deterioration of the political economy and the proliferation of identity politics.

Western politics of resentment can easily be transformed into street politics and populist politics in an electoral system, while the anger infecting Chinese youth becomes instead a mentality of complete resignation and escape into online public opinion. An example of this might be the four “revolts” proposed by the youth on Bilibili: we won’t buy a house, we won’t get married, we won’t have kids, and we won’t work twelve hours a day, six days a week. “If I lie flat, the capitalists can no longer exploit me.” The essence of this resentment is, on the one hand, a legitimate claim against the exploitation of capital; on the other hand, it is an expression of the frustration of a soul that has been captured by consumerism but that remains unsatisfied. This logic does not point to a class narrative, but instead to a welfare narrative similar to what we see in Western social democracies.

Conclusion

Some theorists use the term “new individualism” to attempt to describe the current mentality of Internet youth. In the age of the market economy, individualism is undoubtedly a core aspect of how we understand and live our lives, but the mixture of individualism and nationalism we see in the Little Pinks obviously goes beyond abstract individualism. The “individual” in the thought liberation of the 1980s was a humanist, a spiritually pure individual as imagined by intellectuals. When genuine reform and opening took off in the 1990s, the market economy left these “humanistic individuals” in the dust, and the individual became the abstract “economic man” of Western economics. As the money kept flowing in, these economic men turned into real movers and shakers, a serious blow to the intellectuals’ beautiful imagination of the individual, hence the discussion of the “humanistic spirit ” in literary circles in 1994.

Published in 1998, Liu Xiaofeng’s 刘小枫 (b. 1956)The Weight of the Body is a summary of ideas and ethics in the post-revolutionary era and the period of social transformation, focusing on a discussion of the “pain and happiness” associated with the transformation from a collective ethics to an ethics of individual freedom. However, compared with the Little Pink generation, it would seem that the transformation Liu is discussing occurs only during the transition from the planned economy to the market economy, and the “weight” he discusses does not include the anxiety produced by the gap between rich and poor at the personal level, because the “individual” at that time was not yet fully in touch with housing prices, the cost of education, or problems like overtime and inadequate pay. Nor does it include the experience of direct contact with citizens of the world, which is the experience of young people in today’s era of globalized consumption, at a time when China’s reform and opening is in “deep water.”

After 2008, as China’s rise became increasingly obvious, Chinese people were directly exposed to the global media communication and the competitive emotions this can produce. The Little Pink phenomenon is a manifestation of this. Compared with the equally consumerist “My Little Happiness 小确幸” generation on Taiwan, mainland youth find themselves in an identity war with the West due to China’s rejuvenation, while youth in Taiwan are at ease in the Western international system.

The politics and ethics of the Little Pinks, which reject both intellectualization and proletarianization, are difficult for intellectuals who came of age in the 1980s to accept. They don’t understand why reform and opening and global markets have not only failed to bring about the end of history they had called for, but instead spawned a broader patriotic community. However, the phenomenon of the Little Pinks and all the controversies they have sparked vividly reflect the reshuffling and recoding of various doctrines and ideas in reality, mapping out the symptoms of a post-modernity that is still not here, a history that fails to end, and the last man’s desire for happiness and his continued struggle.

The Little Pinks are a process that to a certain extent goes beyond stoic individualism and “depoliticized politics,” and re-engages with collectivism, nationalism, history, and socialism. The question for the future is: in an era of unprecedented change, will the Little Pink generation rise or fall?

For intellectuals, they first need to shed their posture as outside critics, and reject simplistic terms like “populist” or “backbone 脊梁,” and at the same time, they need to get past stereotypes like “youth” and “mainstream,” and understand that the Little Pinks are not merely a youth subculture, but also the expression of a certain spirit that has been suppressed by intellectuals and by the educational system, and which could only find a place within the youth.

We have witnessed the surge of the Little Pinks’ “force 原力,” but we lack a theory to explain this force. The direction Chinese youth and the new patriotism will take depends on whether the interaction between various intellectual, social, and practical actors can be fruitful. This is also one of the inescapable responsibilities of Chinese intellectuals.